The first serious threat to Richard III’s kingship came in mid October 1483, just four months after his coronation. It is hard now to properly judge the popular reaction to the new king and his seizure of power, but the fact that such a real threat came so swiftly points to some disaffection even during the honeymoon period. As Richard was progressing around his new kingdom refusing gifts of money and contenting “the people wher he goys best that ever did prince”, as Thomas Langton, Bishop of St David’s enthused, others were clearly less upbeat about the new king.

When rebellion came, it was famously to involve Richard’s closest and most powerful ally of the last few months, Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The Duke was to give his name to the uprising, but was this simply an early sleight of hand trick by … well, more on that anon.

Although Buckingham’s Rebellion would fail it is important to understand just how large and well organised a threat it really was and how fortunate Richard was when it finally broke. It is the nature of regimes, especially new ones seeking to put down roots, that rebellion should be understated, but we should not let that blind us to the size and complexity of what was planned.

The rebellion was to take place on 18th October, St Luke’s Day. It is likely people took less notice of the calendar date than feast days in mediaeval times and it is telling that huge royal events always coincided with feast days. So word would have spread that the Feast of St Luke was the day. Kent was set to rise and attack London from the south east, drawing Richard’s attention that way as men of the West Country, Wiltshire and Berkshire, swelled by Buckingham’s Welsh army crossing the Severn and Henry Tudor’s force of Breton mercenaries landing, probably, in Devon moved in from the west. With Richard’s attention on Kent, they would fall on him, catching him unawares, and bring down the might of their combined dissatisfaction upon him.

But how had Richard come to this so swiftly? In June his coronation had been a triumph. He had been well received all around the country, particularly in the north. Perhaps this is precisely where the problem began. Richard was something of an unknown quantity in London, and after the troubles that seemed barely behind them, few can have looked favourably on more uncertain times and more regime change, especially when this new arrival descended from the north and openly favoured the region. There will come a question of self-fulfilling prophecy to add to the cauldron of confusion.

The mystery of Buckingham’s turning of his coat is as fascinating as it is impossible to solve. He may have fallen out with Richard over the fate of Edward IV’s sons, though even this possibility is sub divided, since Buckingham may have been appalled by a plan outlined by Richard to do away with the boys, or Buckingham may have vehemently argued that it must be done only to be denied by Richard. Perhaps Buckingham saw some revenge against the Woodville clan he had been forced to marry into by killing two of its matriarch’s sons. The sources offer as much weight to a prevailing view that Buckingham had killed the boys as Richard had, and Buckingham had lingered in London for several days after Richard left on his progression. Simply, we have no answer to this, only possibilities that warrant examination.

We do know that Buckingham had long coveted the return of the vast Bohun inheritance, withheld from him by Edward IV. Richard was in the process of restoring this to Buckingham, awaiting only Parliamentary approval, but perhaps this was too slow for Buckingham’s liking and fed a niggling doubt that he would ever get it back.

There are two figures who probably do feature prominently in Buckingham’s defection, and possibly play a role that burrows much deeper into the foundations of Richard III’s rule. This inseparable and unstoppable duo are John Morton, Bishop of Ely and Margaret Stanley (nee Beaufort). I know that much is made of Margaret Beaufort’s involvement or lack thereof in, for example, the fate of the sons of Edward IV, but it remains too little examined for me. I have no doubt that many will take objection to what I offer, but I do not present it as fact, merely as a possible interpretation of what happened. I disagree with the view that Margaret Beaufort could not possibly have been involved in anything that went on as much as I do with the view that she definitely killed the boys.

The Tudor antiquary Edward Hall wrote some 60 years later that Margaret Beaufort had chanced to meet Buckingham on the road near Bridgnorth as she travelled to Worcester and he returned to his lands in Wales. She supposedly pleaded with Buckingham to intercede with Richard on her behalf, to use his influence to secure the safe return of her son and his marriage to a daughter of Edward IV, an arrangement that had been close to fruition when Edward suddenly died. There is little of rebellion herein, except that, if this discussion ever took place, Margaret was making it clear to Buckingham that Richard was not one who seemed willing to deliver what had been hoped for under Edward, sowing seeds of doubt that Richard would deliver anything. Of little consequence to Buckingham, perhaps, but he was still hoping for those Bohun lands.

If a seed was sown, it was keenly tended by Bishop Morton when Buckingham reached Brecon Castle. The Bishop had been released from the Tower following the events surrounding Hastings’ execution into Buckingham’s care under a gentle form of house arrest. Morton was mentor to a young Sir Thomas More and it seems likely that More’s version of Richard stems from Morton, a man who seems to have hated Richard with a passion. An ardent Lancastrian, Morton had been reconciled to Edward IV’s rule after Tewkesbury and the death of the line of Lancaster. Buckingham’s family had been staunch Lancastrians too, his grandfather dying at the Battle of Northampton fighting to protect Henry VI. Morton apparently tugged at latent Lancastrian sympathy, perhaps even giving Buckingham hope of the throne for himself. The seed was fertilised and shooting. The Bishop must have been pleased with his work.

This is where many will disagree with my suggestion, but I think it is possible that more cultivating was going on in London at the same time. Margaret Beaufort wanted her son back. She seems to have decided that he would return best by seizing upon the discontent that bubbled around Richard to make himself king. I don’t subscribe to the view that she spent his entire life plotting to make him king, only that she desperately wanted him back and saw an opportunity to good to miss. An all or nothing gamble. But if she was going to gamble her precious only son, she would need to swing the odds as far in his favour as possible.

It is known that Margaret opened a channel of communication to Elizabeth Woodville in her sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. Unable to risk personal visits, Margaret’s physician, Dr Lewis Caerleon acted as a go between, serving Elizabeth as her physician too. By this medium a pact was reached. Elizabeth Woodville would call out her family’s support and, far more importantly, her late husband’s loyal followers, in support of Henry Tudor’s bid for the throne in return for an assurance that Henry would marry her daughter Elizabeth, making her queen if he were successful.

This is a momentous moment in 1483. It marks the acceptance by Elizabeth Woodville that her sons’ cause was dead, and probably her acceptance that they were dead too. She must have been certain of this to offer all of the support she could ever muster to another claimant to what she would have viewed as her son’s throne. Surely she would only do this with certain knowledge of their death. How did she come by this knowledge? Since it was not known throughout London and the country what had become of the boys, and still isn’t to this day, she clearly had ‘information’ we do not. Where did this information come from? It seems likely to me that the source was Dr Lewis Caerleon, passing on sad news from Margaret Beaufort. This does not mean I’m accusing Margaret of doing the deed, or of having it done (though I don’t think that’s as impossible as many like to make out). I am suggesting that she saw an opportunity to improve her son’s chances by feeding a story to a desperate, lonely mother in sanctuary, starved of information and desperate for news of her son. What would better turn the former queen and all of the Edwardian Yorkist support against Richard than news of the death of her sons whilst in his care? The suggestion was probably more than enough.

There, I said it! Margaret lied to Elizabeth Woodville about her sons to secure her support.

As the Feast of St Luke approached, the rebellion looked in good shape. It was large and was a very, very real threat. But then it began to fall apart. The rebellion relied too heavily on everything going to plan. When a spanner was thrown into the works, the carefully constructed machine fell apart. That spanner was thrown when some of the rebels in Kent showed their hand too early. They marched on London on 10th October for some unknown reason, eight days too early. John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, Richard’s loyal friend, was in London. He swiftly saw off the rebels, capturing enough of them to get details of the rebellion planned for the following week.

Richard III was at Lincoln when news reached him on 11th October of the false start, and of the rest of the plan. He called a muster at Leicester and set out to crush the rest of the waiting rebels. Orders were sent for bridges over the Severn to be destroyed to prevent Buckingham from leaving Wales and the border region was ordered to resist any attempt by Buckingham to cross it.

On 18th October, the plan swung into action, but the weather now seemed to work in the king’s favour, no doubt a sign of God’s favour in the days when men were keen to see signs wherever possible. A tremendous storm battered England. It rained for ten solid days. The River Severn was swollen and ferocious, bursting its banks at many points. With bridges slighted, Buckingham could find no crossing and his less than keen Welsh levies were happy to desert him in favour of home and hearth.

In the Channel, Henry Tudor’s fleet had been scattered by the same storm. When his ship, possibly alone, at most with one other left for company, finally reached the south coast, he was hailed by a group of soldiers as a victorious conqueror. Buckingham had, they called from the shore, succeeded in full and now keenly awaited Henry’s arrival. Ever astute and suspicious, it is not hard to picture Henry narrowing his eyes in the driving rain just off the coast. If it sounded too good to be true, it probably was. Henry turned his ship about and aimed it back at Brittany. His shrewd caution doubtless saved his life.

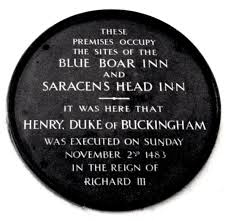

Buckingham was forced to flee, taking refuge in the house of one of his men, Ralph Banastre. Before long, the promise of a hefty reward caused Banastre to hand Buckingham over to Sir James Tyrell, who escorted the Duke to Salisbury. Buckingham supposedly begged for an audience with his erstwhile friend the king. Richard resolutely refused to allow the Duke into his presence. The feeling of betrayal was plain when, at news of Buckingham’s part in the rebellion, Richard wrote from Lincoln to John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln, requesting that he send the Great Seal, raging in his own hand against “the malysse of hym that hadde best cawse to be trewe, th’Duc of Bokyngham, the most untrewe creatur lyvyng”, adding that “We assure you ther was never false traytor better purvayde for”. To a man who seems to have seen things in black in white, this betrayal of trust was utterly unforgivable. Though this facet of Richard’s character was to cause him great problems in other ways, it probably served him well in this case. Buckingham was beheaded as a traitor in Salisbury market square on 2nd November.

So, it seemed, Richard had swiftly, decisively and effectively crushed the first uprising against his rule. Buckingham was dead. Tudor had scurried back to Brittany, though evaded capture. It was clear that Morton and Margaret were heavily involved in the plot, and it must have seemed as though God had sent the storms to thwart Richard’s enemies, proving that he was the true king, chosen by God.

How Richard dealt with the aftermath of this rebellion was to be key. And I think that he dealt with it poorly.

Morton escaped, fleeing first to the Fens and then taking a ship to Flanders where he hid from Richard’s vengeance and continued to plot. Margaret Beaufort, though, was cornered. Richard’s response to her part in the scheme to place her son upon his throne is remarkable, particulary for those who view Richard as a merciless, ruthless tyrant. Margaret was, in effect, let off. Her lands were forfeit, but were granted to her husband, Thomas Stanley, the same man Richard had arrested as a traitor in June. She was placed under house arrest in her husband’s care. He was to make sure that she made no contact with her son. I can’t imagine what assurances Stanley offered to make Richard believe that he would do as instructed. It was Richard’s mercy, and perhaps naivety, that sealed his fate. Beheading women would have to wait for the Tudor era.

My suggestion is that from the very outset of Richard’s rule, Margaret Beaufort spied an opportunity. If she could not have her son returned to her by peaceful means, then she would craft for him the opportunity of the grandest possible return to England. Perhaps she fed Elizabeth Woodville lies to make her believe that Richard had killed her sons, whether Margaret was aware of their true fate or not. The revelation of the truth could then be what drew Elizabeth and her daughters from sanctuary to Richard’s court a few months later. Whether that revelation was of her sons’ murder at the hands of another, perhaps Buckingham, or of their survival we cannot know, but this version of events at least helps to make her actions more understandable.

This is to view Buckingham’s rebellion as a thin veil drawn over a Tudor plot. His name given to protect others because his life was lost. The extent of these roots may be larger than we know and stretch right back to the very beginning of Richard’s rule. How much of the disaffection against Richard in the south was stirred up deliberately, planting and cultivating opposition to Richard in order to reap support for Henry? It took two years longer than hoped, but the harvest came in finally.

Opposition to and resentment of Richard’s rule only grew when he reacted to the south’s revolt by planting his loyal northern allies across the south. This is perhaps the self-fulfilling prophecy that I mentioned earlier. If men feared Richard would force his northern friends into their region, they made it a certainty by rebelling. If Margaret had used this fear to ferment opposition, Richard played into her hands by doing precisely what the southern gentry feared most – taking their land, money and power away from them. But what choice was Richard really left with? Already, he was being forced to paint himself into a lonely corner. I just wonder how much of this was some overarching Tudor scheme.

I remain unsure whether the sleight of hand here was the work of Richard, to disguise Tudor’s threat, making Buckingham the prime mover and demonstrating his fate, or that of Margaret Beaufort, Thomas Stanley and Henry Tudor, concealing the threat they still hoped and intended to pose.

Ricardians will lament the missed opportunity to remove Stanley in the Tower in June and Margaret following this uprising in October. Without their driving force, determination and resources, would Tudor ever have reached England again? It is testament either to Richard’s naivety, their cunning, or both that they survived to see him fall at Bosworth two years later.

Matthew Lewis is the author of a brief biography of Richard III, A Glimpse of King Richard III along with a brief overview of the Wars of the Roses, A Glimpse of the Wars of the Roses.

Matt has two novels available too; Loyalty, the story of King Richard III’s life, and Honour, which follows Francis, Lord Lovell in the aftermath of Bosworth.

The Richard III Podcast and the Wars of the Roses Podcast can be subscribed to via iTunes or on YouTube

Matt can also be found on Twitter @mattlewisauthor.

Brilliant blog as ever Matt. Interestingly – just bought a book which states Richard was in Grantham when he heard about the rebellion and requested the Great Seal. I had always read Lincoln..,have you come across the Grantham reference before?

Thank you very much. I haven’t seen Grantham mentioned.

It’s The Companion to the Wars of the Roses – by Peter Bramley. He states Richard was at the Angel and Royal Hotel in Grantham when he learned of the rebellion and wrote the letter for the seal. I have only come across this here – every other source I have read states Lincoln.

Yes, I believe he was at ‘The Angel and Royal’ in Grantham when he received the news. I have been there and in the very room, it is now a lovely restaurant.

Excellent, Matt

When you put it like that, who can argue

Pat

Intriguing post! I’ve read Margaret Beaufort persuaded Elizabeth Woodville to join the rebellion by assuring her the country is disgusted at the ‘usurpation’ by Richard, that Henry can bring an army from France, (possibly backed by a Stanley army) in order to kill Richard then release and crown the Prince in the Tower. The payback would be for Henry to be given a high level position at court.

Woodville may have accepted this as she, and many others may not have believed Henry’s ambition would reach the level of coveting the throne itself.

I keep coming back to another unanswerable question about Woodville’s actions. There is evidence for her support of the Simnel Rebellion later in Henry’s reign. Why on earth would she want to support a rebellion designed to oust her daughter as queen unless one of her Princes was alive? What’s better than your daughter on the throne? A son as king is!

Another excellent blog Matt, coming as it does around the anniversary of the Battle of Bosworth. It is with that in mind that I was stuck, despite the information not being new, by reading about the slighting of the bridges over the Severn. Why would Richard not order the same action 2-years later? Was it as a result of the information from the premature men of Kent or astute tactical thinking. Did he not have access to such information 2-years later, or was the force adjudged so inconsequential that a good battle was just what was required to reassert his rightful claim?

Thank you for your kind comment. The question about bridges in 1485 is a good one. From Richard’s reportedly excited response to the news of Tudor’s landing it would seem that your final thought is quite likely – Richard wanted to meet Tudor in Battle and destroy the final threat to his crown personally and definitively.

Excellent, thought provoking post as usual Matt. Have just finished reading’Honour’ while staying just next to Middleham Castle ….. again who knows what happened but one can’t help thinking ‘if only…..’ Very poignant and atmospheric place to read such a book – especially to learn that here was a muster at Masham just down the road in 1487.

I have no doubt in my mind that MB and Morton were the chief instigators in all of this, their ultra craftiness and sly whispering campaigns were too much for Richard who lived his life by ‘doing the right thing’ and could not or would not comprehend that others were not as loyal and truthful as he was.

Thank you for your kind comments. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. I hope you enjoyed Honour too. Part of the interest of this whole period, and most of the frustration of it, is that so much is open to interpretation at polar opposite ends of the argument. The same fragment of half information can be used to argue any persons guilt and their innocence.

If you did enjoy Honour, I would really appreciate a review on Amazon if you have time and don’t mind. As a self published author they are still my best form of advertising.

Many thanks.

Matt

Thank you for the lovely review. It is very much appreciated.

Matthew, I thoroughly enjoy your erudite and well-written articles about Richard III and the Wars of the Roses. I have never felt the need to post a comment before because you cover the subject so comprehensibly that there is little to say except ‘I agree’.

However, your recent article on Buckingham’s rebellion has given me pause for thought: in fact, I am puzzled. My concern arises from your accusation that “…Margaret lied to Elizabeth Woodville about her sons to secure her support”.

My question is this: what exactly was her lie? Are you saying that Margaret just invented the story of their death and, presumably, blamed Richard? Or are you alleging that she had certain knowledge of their death because she and others were involved in its commission, and that her lie was to blame Richard? You seem to have skated around this issue in the article presumably in an effort to appear fair and balanced. That is all well and good, except that it leaves me wondering what your conclusion is.

My concern is not merely academic; the notion that the boys were dead by Sep 83 is inherently prejudicial to Richard. First, because it is a presumption, which is not supported by any credible ‘evidence’ and second, because it makes Richard culpable even if he is not their killer, or even knew about it. We should not ask ‘who killed the Princes’ but “what happened to the them’. The only verifiable fact we have is that they were not seen in public after the late summer and/or autumn of 1483: they had disappeared. Whilst this is, of course, consistent with their death, it could equally be that they were sent abroad to live in obscurity.

My personal opinion is that the October conspirators simply did know what had happened to the Princes; ex hypothesi, they cannot be guilty of murdering them. The fact is that we don’t even have a plausible explanation of how precisely they might have done that. But even more conclusive to me is the evidence of Henry’s actions and behaviour after Bosworth. I believe his failure to allege regicide against Richard in the Act of Attainder, his failure to produce and display their bodies (any juvenile corpses of similar ages would have done), and his almost paranoid concern with ‘feigned’ boy pretenders, is incompatible with certain knowledge of their deaths. I also believe that the rumour that ‘arose’ (or ‘was spread’, depending on which translation of Croyland you prefer) after Buckingham joined the conspiracy was false; it was started deliberately to subvert what was a localized southern conspiracy to free the Princes into a full-blown rebellion to depose king Richard III. Of course, my theory is only tenable if one accepts that at some point in during the late summer or early autumn of 1483 the boys did disappear from public view and knowledge. My personal explanation is that they removed to a place of safety after the July and August plots, at Richard’s bidding. Buckingham and/or Margaret Beaufort discovered the boys has disappeared: none knew where. They then concocted a very clever trick to either flush them out or to put Richard in the dock. When the rumour was started he could either produce them or take the blame. Producing them was impossible because he knew their fate once his enemies knew they were alive; so, he took the blame. It is AN explanation, though I accept that it is not

necessarily THE explanation.

Hi Trevor,

Thank you for your kind words about the blog. I’m glad that you enjoy it, and sorry if this has left an unsatisfactory gap. I wasn’t trying to skirt the issue, my assertion is that Elizabeth Woodville’s support for the rebellion and the marriage of her daughter to Tudor can only mean that she believed her son’s were beyond salvation. From sanctuary, how would she gather this belief? We know for certain that Dr Lewis acted as a go-between, sent by Margaret. That (at least) suggests to me that Margaret could have sent the doctor to mislead Elizabeth, with false news of her sons’ deaths at Richard’s hands. I don’t believe they were dead, but whether they were or not, no one knew for certain and perhaps Margaret seized on the uncertainty to solemnly confirm Elizabeth’s worst fears as she sat in her seclusion, desperate for news.

The lie was that Margaret knew what had happened, and that the boys were dead. This lie would make sense of Elizabeth’s support of Tudor in October 1483, and then of her return to Richard’s court in Spring 1484. She found out the truth.

Of course, this is just conjecture, and only my attempt to unravel the confused events. I hope that makes it more clear.

Thank you again for reading and for your comment.

Matt

Until the finding of Richard III’s remains, I was a pretty staunch Richard supporter. But the way the body was left makes me fear that he was much more hated that I had previously believed. He was a king, after all, and to allow his body to remain as it was, discarded, with no one claiming it, ever, I find indefensible. Even during the Tudor reigns. Surely locals knew where it was. Why did no one intervene to re-bury him? I find it tragic.

Thank you Matthew for clarifying that for me. I am back on an even keel now

Trevor

Matt, this is Nov 24, 2014 and I am kind of late to the party on this one. I enjoy your writing, and purchased your book, :”Loyalty”. I wanted to comment on Elizabeth W’s raprochement with Richard. You seem to think it a sign that she thought Richard was “all right” after all. Hadn’t she been in sanctuary with a bunch of bored kids for quite a while at the time? Didn’t Richard have armed men all around the Abbey 24/7? Wasn’t he pressuring the Abbot constantly to give Elizabeth up? And didn’t she require Richard to publicly swear that he would not hurt her or the children, or imprison them in the tower, etc etc before she came out? That doesn’t seem to me as though she didn’t see him as a threat.

Hi Jo Anne. Thank you for your comment. I hope you enjoy Loyalty.

I dont have any definite answers about Elizabeth Woodville’s emergence from sanctuary. No one can be sure what caused her change of mind, but I would think it odd, whatever the pressure, for a mother to hand her remaining children over to a man who she believed had murdered her sons. Richard did take an oath not to allow her daughters to come to any harm, but if Elizabeth had reason to believe him a murderer, why not an oathbreaker too? Why not remain in sanctuary so that Richard would have to show his hand by breaching the sanctity of that place openly? Why summon her son, the Marquis of Dorset, back from Henry Tudor’s court if Richard was a murderer? Thomas was not stuck in sanctuary, but was safe overseas.

It can also be argued that Elizabeth had no hope and that her daughters were no threat, but the eldest was betrothed to Henry Tudor, his prize if he could seize Richard’s throne. Yes, the invasion in 1483 failed, but Tudor was still at latge to try again, so Elizabeth did have some hope, and her eldest daughter was a serious threat.

I don’t know why there was an apparent concord reached. It defies almost any explanation in which Richard was even suspected of having killed the two boys, so I am looking for another explanation.

I don’t know, though. That’s such a large part of the frustrating, fascinating enigma of Richard III.

Why don’t we just call it the Beaufort – Woodville Conspiracy because that’s exactly what this was? Buckingham just happened to have the men and outside contacts, the weapons and his own disaffection with Richard. He would have set himself up as King if he could rally enough support. He backed Henry Tudor because that’s what the two leaders aka Margaret and Elizabeth W wanted and it suited his purposes. If Henry landed and won great, he might get more recognition but if Henry failed his own claim could be put forward. He was the same age as Henry Tudor, had a better claim and a family. He would do as a stand by or fall guy. He was also brutal and he would not think twice about killing the sons Edward iv. If Buckingham failed, there was still the claim of Henry Tudor who escaped and would try again. If both men joined together and defeated Richard, one could be disposed off, hopefully Buckingham would be done away with and Henry arrive with a huge French army and Margaret and Elizabeth see their plans fulfilled. That was the dream but in reality this was bound to fail because it was not one linked plot but several which the protagonists hoped could come together somehow. I also agree that if this was the point that the Queen was told her sons were dead or heard by rumours, then the aims changed. The original plan was probably to free and restore Edward V with backing turning to Henry in the Autumn at the time of the Rebellion. Richard was well on top of things before then and it was only a matter of time before the whole thing crashed down on them.

You are correct about Richard, by sparing so many people he set himself up for betrayal. A traitor is always a traitor and needs dealing with.