I read a series of blog posts recently that sought to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Richard III ordered the deaths of his nephews. Whilst I don’t take issue with holding and arguing this viewpoint I found some of the uses of source material dubious, a few of the accusations questionable and some of the conclusions a stretch. There are several issues with the narrow selection of available sources that continually bug me. It is no secret that any conclusive evidence one way or another is utterly absent but I have issues with the ways the materials are frequently used.

There are four main sources that are often used, two contemporary and therefore primary sources and two near-contemporary which are habitually treated as primary. The farthest away in time from the events that it describes is also the one traditionally treated as the most complete and accurate account, which in itself should urge caution. Sir Thomas More is believed to have started writing his History of King Richard III around 1513 when he was an Undersheriff of London and the first thing to note is that he never actually published the work. It was completed and released in 1557 by More’s son-in-law William Rastell. It is unclear what parts of the History Rastell finished off but More’s account became the accepted version of the murder of the Princes in the Tower for centuries, heavily informing Shakespeare’s play on the monarch. More was just five years old during the summer of 1483 but may well have had access to people still alive who were better placed to know what had happened – or at least, crucially, what was rumoured to have happened, for much of the work reports rumour and opinion rather than fact and is quite open about that.

The next thing that screams out from the opening lines of More’s work is an error, unabashed and uncorrected. We are informed in the very first sentence that ‘King Edward of that name the Fourth, after he had lived fifty and three years, seven months, and six days, and thereof reigned two and twenty years, one month, and eight days, died at Westminster the ninth day of April’. Edward IV actually died nineteen days shorts of his forty-first birthday. This glaring error is frequently excused by the suggestion that More must have meant to fact check his work later but this proposition is usually made by the same readers who insist that More was a fastidious, trustworthy man who would not have lied nor scrimped on ensuring the veracity of what he wrote. These two arguments appear to me to be mutually exclusive. This is the first sentence of More’s work. Would he really have guessed, giving such a precise figure that he didn’t know was correct, as the first words of his work? Edward was king for twenty-two years, one month and five days (ignoring his brief sojourn in Burgundy), so More shows us that he can get these things right if he wants to (albeit still 3 days out). Why not insert a placeholder of ‘about fifty-three years’ or a gap to be filled in when the correct number could be found? The number of years is wrong, the number of months is wrong and the number of days is wrong. How could this have happened?

What if More’s work on Richard III was also intended to be allegory? Perhaps it was too unsubtle or proved unsatisfactory and was replaced by Utopia, or maybe they were meant to be read side by side. Like Shakespeare, was More using Richard III, a figure from the near past who could be vilified in any way that suited the writer because he had no connection to the throne any longer. Henry VIII had Yorkist blood from Edward IV but not Richard III, so he was fair game and so close in time that his story could be an almost tangible warning against tyranny and the murder of innocents. It is frequently overlooked that Henry VIII’s tyranny began at the very outset of his reign, not after a couple of decades. One of his first acts on succeeding his father was to arrest Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, two of his father’s closest advisors and most effective revenue generators. This had made them deeply detested and Henry grasped an opportunity to make a popular statement as soon as he became king. A tyrant will bypass justice for two main reasons; security and popularity, and Henry VIII executed these men ostensibly for doing as his father had instructed them, even though they had not broken any law, whilst still in his teens simply for the popularity it would bring him. What, then, if More began his History of King Richard III as a renaissance tract on the dangers of tyranny and the murder of innocents? Was he warning Henry VIII that killing men without the due process of law could only end badly? His failure to publish it might be explained by his promotion to the Privy Council in 1514. More was never afraid to criticise the Tudor establishment, opposing Henry VII in Parliament, and perhaps he felt he could now get close enough to deliver the message of his book in a more direct way.

On the death of Henry VI, More wrote of Richard III that ‘He slew with his own hands King Henry the Sixth, being prisoner in the Tower, as men constantly say, and that without commandment or knowledge of the King, who would, undoubtedly, if he had intended such a thing, have appointed that butcherly office to some other than his own born brother.’ Still More only reports rumour – ‘as men constantly say’ – and the claim that Edward IV was unaware that Henry VI was to be killed is ludicrous. It remains possible that Richard, as Constable of England, arranged the death and perhaps even that he carried it out himself, but Edward must have given the order. If he hadn’t, where was the punishment or censure for unauthorised regicide? Richard was the natural choice. Who but a brother of the king might be permitted to perform the deed? A commoner could not be allowed to kill a king, for he might chose to do it again and the majesty of the position would be dangerously undermined. Richard was not only Edward’s brother he was a man the king trusted implicitly. Is this another signpost that More was not writing the whole truth but something that needed to be looked at a little closer?

Returning to 1483, More wrote of the sermon on the illegitimacy of the Princes that ‘the chief thing, and the most weighty of all that invention, rested in this: they should allege bastardy, either in King Edward himself, or in his children, or both, so that he should seem unable to inherit the crown by the Duke of York, and the Prince by him. To lay bastardy in King Edward sounded openly to the rebuke of the Protector’s own mother, who was mother to them both; for in that point could be none other color, but to pretend that his own mother was one adulteress, which, not withstanding, to further his purpose he omitted not; but nevertheless, he would the point should be less and more favorably handled, not even fully plain and directly, but that the matter should be touched upon, craftily, as though men spared, in that point, to speak all the truth for fear of his displeasure. But the other point, concerning the bastardy that they devised to surmise in King Edward’s children, that would he be openly declared and enforced to the uttermost.’ More claims, then, that there was some subtle suggestion that Edward IV was a bastard but, to avoid offending his mother, Richard did not make this too plain nor did he rely upon it. The charge that the princes were illegitimate was the crux of his plan. More makes another error by naming the subject of the pre-contract as Dame Elizabeth Lucy rather than Lady Eleanor Butler. Another blatant error in an account we are supposed to rely upon completely by a man above reproach?

On the murder of the princes, More details Sir James Tyrell’s part in the deed on behalf of a king terrified for his own security (a man who becomes more and more like Henry VIII himself). This has long been the accepted and authoritative account, used to prove Richard’s guilt and that the human remains resting in Westminster Abbey are those of the Princes in the Tower, discovered precisely where More said they would be. Of course, that completely ignores what More actually said, which was ‘ he allowed not, as I have heard, the burying in so vile a corner, saying that he would have them buried in a better place because they were a king’s sons. Lo, the honourable nature of a king! Whereupon they say that a priest of Sir Robert Brakenbury took up the bodies again and secretly buried them in a place that only he knew and that, by the occasion of his death, could never since come to light.’ More categorically states that the bodies were not left beneath a staircase in the Tower of London. If he had this wrong, then how are we to rely on his other evidence (if we were ever meant to)?

Sir Thomas provides further detail to back up his story of the murder, claiming ‘Very truth is it, and well known, that at such time as Sir James Tyrell was in the Tower – for treason committed against the most famous prince, King Henry the Seventh – both Dighton and he were examined and confessed the murder in manner above written, but to where the bodies were removed, they could nothing tell.’ I was once told that anyone who begins a sentence with ‘To be honest’ is probably lying. There is no record other than More’s claim that Tyrell was ever even questioned about the murder of the boys, let alone that he confessed. The holes in the story are compounded when More writes of the killers ‘Miles Forest at Saint Martin’s piecemeal rotted away; Dighton, indeed, walks on alive in good possibility to be hanged before he die; but Sir James Tyrell died at Tower Hill, beheaded for treason’. Wait – Dighton walks the streets? The Dighton who confessed to murdering two young boys, two princes, with Sir James Tyrell? So, after his confession he was sent on his way? Surely that is beyond ridiculous. Perhaps it is more likely that this is some political comment on the state permitting killers to roam free. A story recently emerged suggesting that Elizabeth of York and Henry VII’s attendance at Tyrell’s trial at the Tower of London prove a connection with the princes. Henry and Elizabeth were at the Tower at the time of the trial. Why else but to find out the fate of her brothers? For this to stack up we would need to ignore the fact the Tyrell was tried at the Guildhall.

It is frequently claimed that More had inside knowledge as well as access to those alive during 1483. Thomas was, for a time, a member of the household of Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and nemesis of Richard III. It has been suggested that More’s manuscript was actually the work of Morton or at least that Morton gave More vital information. To accept this is to believe that Morton deliberately withheld crucial information from Henry VII whilst allowing him to suffer constant threats from Warbeck and other pretenders. Not that I think Morton above such a manoeuvre.

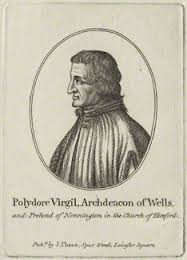

The second near-contemporary source was written by Polydore Virgil. Its veracity is questionable because Virgil was commissioned by Henry VII to write it, but it is often given plenty of weight. His story differs from More’s in relation to the sermon delivered by Dr Ralph Shaa, of which Virgil wrote ‘Ralph Shaa, a learned man, taking occasion of set purpose to treat not of the divine but tragical discourse, began to instruct the people, by many reasons, how that the late king Edward was not begotten by Richard duke of York’, claiming only that the charge was of Edward IV’s illegitimacy and making no mention of the pre-contract. Why might he have claimed his patron’s father-in-law was a bastard? Probably because it was not a charge that was taken seriously, but the illegitimacy of the princes led to their removal from the line of succession and would have tainted Henry VII’s wife Elizabeth and their children too.

The two contemporary sources are, in many ways, equally problematical. Dominic Mancini was an Italian visitor to London during the spring and early summer of 1483 and his evidence is usually considered of particular value because he was a foreign eye witness with no axe to grind on either side. This easy reliance ignores key aspects of Mancini’s work, not least its title. Usually given as ‘The Usurpation of Richard III’, the full Latin title is actually ‘Dominici Mancini, de Occupatione Regni Anglie per Riccardum Tercium, ad Angelum Catonem Presulem Viennensium, Libellus Incipit’. Two things are significant here. ‘De Occupatione’ does not translate as The Usurpation but as The Occupation – The Occupation of the Throne of England by Richard the Third. Latin has words for usurpation, but none are used here and the title becomes a whole lot less sinister when the word Occupation is used.

The second significant item within the title is the identity of Mancini’s patron. Angelo Cato was Archbishop of Vienne and it was for him that Mancini’s report was penned. This is significant because Cato was a member of the French court, serving as personal physician to Louis XI for a time. This connection is crucial because Richard was a figure known to the French court and of interest to the cunning and wily Louis, who must have marked Richard as a man to watch after Edward IV’s campaign to invade France. Richard had disagreed with his brother’s decision to make peace and refused to attend the signing of the peace treaty. Louis had managed to secure a private meeting with Richard later, probably to size him up. Mancini was writing for a man close to Louis who would have had an image of Richard coloured by that relationship and this must impact both Mancini’s account and the reliance that we can place upon it. Mancini makes several errors that betray a lack of understanding of English society, politics and culture that lessen his reliability but the identity of his patron cannot be ignored too.

Our other contemporary source is the redoubtable Croyland Chronicle. Although the author is anonymous he is understood to be very close to the Yorkist government and has been tentatively identified as Bishop John Russell, Richard III’s Chancellor. A trusted member of Edward IV’s government it is believed that Russell accepted the position of Chancellor only reluctantly after Bishop Rotherham was dismissed. Russell remained Chancellor until Richard III dismissed him in July 1485, shortly before Bosworth. The Croyland Chronicle continuation with which he is credited is believed to have been written shortly after Bosworth at the outset of Henry VIIs reign. Certainly the Croyland Chronicle is not favourable to Richard, criticising the vices of his court, particularly at Christmas, though this was the conventionally pious opinion of the Church.

On the subject of the sermon by Ralph Shaa, Croyland recorded that ‘It was set forth, by way of prayer, in an address in a certain roll of parchment, that the sons of king Edward were bastards, on the ground that he had contracted a marriage with one lady Eleanor Boteler, before his marriage to queen Elizabeth; and to which, the blood of his other brother, George, duke of Clarence, had been attainted; so that, at the present time, no certain and uncorrupted lineal blood could be found of Richard duke of York, except in the person of the said Richard, duke of Gloucester’. The coldly factual account makes no mention of an accusation laid against Edward IV, though this might be because Russell (if he was the author) would not give credence to such a claim against his former master. However, if that were the case, why record the allegation regarding his marriage and his sons? Why one and not the other when surely, if both were made, both or neither would have been recorded? Croyland’s evidence, when weighed with the other accounts available, would lead me to conclude that Ralph Shaa preached on the existence of a pre-contract and the illegitimacy of the princes but made no mention of Edward IV’s illegitimacy.

On the fate of the princes, Croyland offers the story that in late summer ‘public proclamation was made, that Henry, duke of Buckingham, who at this time was living at Brecknock in Wales, had repented of his former conduct, and would be the chief mover in this attempt, while a rumour was spread that the sons of king Edward before-named had died a violent death, but it was uncertain how’. Croyland seems to be explaining that a rumour that the boys were dead was deliberately created and spread as part of Buckingham’s Rebellion (which was, in fact, Henry Tudor’s Rebellion as discussed in a previous post). Nowhere does he, well-informed as he undoubtedly was, possibly at the very centre of Richard’s government, state that they were dead or that Richard ordered them killed. Writing under Henry Tudor, he would have nothing to fear from the accusation and everything to gain from a new king keen to know the fates of potential rivals. Why would such a well-informed man never once state that they were murdered? Perhaps because he knew a secret his new king would not like, that would only increase his insecurity. There is another source, uncovered amongst the College of Arms’ collection in the 1980’s that refers to a story that princes were murdered “be [by] the vise” of the Duke of Buckingham. Though there is discussion as to whether ‘vise’ should mean advice or device, there is nevertheless more evidence to relate Buckingham and his revolt to the death of the boys. Perhaps this ties in with Croyland’s tale but the rumour became confused, or perhaps it is the truth.

Based upon what Croyland says, the pre-contract story was the reason the princes were declared illegitimate, was the only story given and must have been in circulation and widely believed enough to cause men of power to petition Richard III to take the throne. His silence on the matter of the fate of the princes is also frustrating but revealing. He claims that there was only ever a rumour of their deaths as part of a planned rebellion, never actually stating that they were dead, let alone that Richard ordered their murder.

Our only other guidance is the actions of those living through the spring and summer of 1483 in London. For example, Elizabeth Woodville’s eventual emergence from sanctuary in 1484 has always been problematical. If she knew that Richard had murdered her sons by Edward IV, why hand over her daughters like lambs to the slaughter? Richard promised to take care of them, but what does the word of a child murderer mean to their mother? The fact that Richard had, in fact, ordered the killing of one of Elizabeth Woodville’s sons is often cited and the question asked as to whether she would have valued a royal son more highly than a non-royal son, but this question is frequently asked by the same people who believe that Elizabeth Woodville emerged because she was so utterly ruthless that even knowing Richard had now killed three of her sons she could not bear to stay in sanctuary indefinitely even to keep her daughters safe. The executions of Richard Grey, along with Anthony her brother, were very different matters. They were not, as I have seen stated, illegal, since Richard was still Constable of England and within the law to order their executions. They were found guilty of treason and their deaths far more legal than those of Elizabeth’s father and another brother at Warwick’s hands. Richard had used the law to publically kill Richard Grey. If he had killed the princes it would have been utterly illegal and illicit. Elizabeth might have been able to stomach the loss on the former basis that had characterised her life, but surely not the second. She might feel comfortable giving herself and her daughters over to a man who would kill if the law allowed or required it, but surely not to a cold killer of children in secret. Her actions make far more sense if she had some concrete evidence that her sons by Edward IV had not been harmed in secret and outside the law. Only then could she be sure her daughters were in no danger. Girls were no threat, some say. That is to ignore the fact the Henry Tudor had sworn to use one of them to take Richard’s throne from him. They were every bit as much of a threat as their brothers.

Then there is the fact that Richard did not, by any measure, usurp the throne of England. He was petitioned to take it by a delegation nominally representing Parliament (though it is important to note that Parliament itself was not in session at the time). If these men had seen evidence of the pre-contract then they accepted it and asked Richard to be king because he was the only rightful candidate. I don’t buy the idea that they cowered in fear from an armed force that was on its way. Powerful men in the country and the City were never so easily cowed.

There is one more reason that Thomas More might have written such a condemnation of Richard III. What if it was a smokescreen, as suggested by Jack Leslau and detailed in a previous post?

Matthew Lewis’s has written The Wars of the Roses (Amberley Publishing), a detailed look at the key players of the civil war that tore England apart in the fifteenth century, and Medieval Britain in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing), which offers a tour of the middle ages by explaining facts and putting the record straight on common misconceptions.

Matt is also the author of a brief biography of Richard III, A Glimpse of King Richard III along with a brief overview of the Wars of the Roses, A Glimpse of the Wars of the Roses.

Matt has two novels available too; Loyalty, the story of King Richard III’s life, and Honour, which follows Francis, Lord Lovell in the aftermath of Bosworth.

The Richard III Podcast and the Wars of the Roses Podcast can be subscribed to via iTunes or on YouTube.

Matt can also be found on Twitter @mattlewisauthor and on Facebook.

Reblogged this on murreyandblue and commented:

Some thoughts on source material about events of 1483, the pre-contract and murder.

Lots of very interesting analysis, and logical explanation of sources. If only some new, undiscovered documents would turn up in some archive, to set the matter straight once and for all!

Thank you. I’m still holding out for Richard III’s diary!

Brilliant and insightful as usual Matt and a great relief after watching Dan Jones last week. I really fear for what people will take from that series! One thing that has always puzzled me is Tyrell. If he was really involved in the murder of the princes – after Richard was killed at Bosworth – he could have done his new king a great service by telling Henry that he had been ordered to kill the princes at the former evil kings command! This would then have saved Henry the problematical insecurities caused by the Simnel and Warbeck rebellions. Why did the man wait 17 years to “confess” – when he could have done his new king a true service and ingratiated himself at the same time. I am sure Tudor would have rewarded him rather than punished him for confirming what a tyrannical murderer King Richard had been.

I recall the story about Henry and Elizabeth’s visit to,the Tower – as I recall the “new evidence” of the historian who brought it up. Why did Richard kill the princes? Where’s the evidence? Apparently “he would have been a fool not to.”

Can see that premise standing up well in a court of law!

Thanks Matt – keep it up!

Richard Marius and Peter Ackroyd, two of Thomas More’s biographers, have suggested that his Richard III was not intended as a serious biography. Also, I understand that Vergil is the only source for the story that Elizabeth Woodville not only put her daughters in Richard’s care (after he took a public oath to treat them well and find them gentlemen to marry), but she also wrote to her one surviving son, telling to come home and make his peace with Richard. Is this correct?

Yes, Elizabeth Wydville DID write her surviving son Thomas (later Marquess of Dorset) and told him to come home, where he would be treated fairly. However, Henry Tudor had him “detained” and he was actually held as a hostage in France until after Bosworth. He was the great-grandfather of Lady Jane Grey. (Thomas 1st Marquess>Thomas 2nd Marquess>Henry 1st Duke of Suffolk>Lady Jane Grey.) Henry Tudor never trusted him, and Grey was periodically imprisoned to remind him that he no longer had any real influence.

Oh, and I forgot to add that Richard did keep his word to Elizabeth regarding her daughters: he arranged a marriage for Cicely in 1484 with Ralph Scrope, the future Baron Scrope of Masham. He was close to her in age – unlike the husband Henry Tudor provided her with after he had the Scrope marriage forcibly annulled: Henry’s half-uncle John Welles who was nineteen years her senior. Cicely’s oldest sister was part of the double-marriage arrangement with the Royal family of Portugal: she was intended for Manuel Duke of Beira, later King Manuel I, while King Richard himself was to marry the Portuguese King’s sister Joana. Of course Elizabeth married Tudor instead. The younger girls were also married to Tudor supporters except for Bridget, who became a nun.

Excellent article and arguments. Two more things have always stood out for me:

1. No funeral mass was ever said for either boy. Not at Elizabeth Woodville’s order, or Elizabeth of York, or even Henry VII. To order a funeral mass for someone alive simply wasn’t (and still isn’t) done.

2. For Richard to have ordered the boys killed and then not to have displayed their bodies would have been the height of stupidity, and stupid is something Richard’s critics have never claimed him to be. The entire point of displaying an enemy’s body was to prove the person was dead, specifically to discourage and/or prevent any uprising in the enemy’s name.

Exactly. If Richard had been involved with their deaths, however peripherally, the boys would have “perished” in a tragic accident or of a sudden illness, poor things, and been given a beautiful funeral and requiem mass. Having them just disappear benefited no one except Henry Tudor.

Excellent as usual Matthew! Thank you.

Have you had any more thoughts on the boys being taken to Colchester by Lovell after Bosworth? H7 paid much attention to the place I think and Abbot Stanstead was a Yorkist sympathiser? Plus, didn’t Katherine Gordon send money to the Abbey for some years? I would love to unearth more about this possibility.

Matt,I already published several articles about the FACT that not only Richard,but Shakespeare is also outrageously maligned in connection with this.Anyone can read the one I published online on Queen Anne Boleyn.com.Shakespeare’s grotesque parody,Richard lll is misinterpreted together with his whole oeuvre,just to do favours to the victorious Tudor dynasty.In the book I will publish this year,I suggest that More is also misinterpreted. He didn’t publish his Richard lll,because he was looking for the way to make clear that he was writing about malicious rumours,but he himself was killed by a Tudor,and his work published irresponsibly after his death.Please, everyone, read Rumour at the beginning of Shakespeare’s Henry lV.And who is daft enough to take literally what Buckingham,son,says about the death of his father in the play of Shakespeare and Fletcher, Henry V lll? It is one of the sickening speeches the monarch’s victims were forced to make before their beheadings! All this will be in my new book.

I am fed up with the power worshippers who keep on insulting Richard because he literally fell out of power. If he had ordered the killing of the boys,it would not have been so unique,most kings did similar things,the Tudors more than anyone else.This is what we should answer to the power worshippers.

More things about More : if I remember well, I even mentioned in one of my previously published articles that More didn’t mean to write about ‘history’ repeating over and over again that men ‘deem’.In my new book,,Shakespeare Made Me Love Richard III, I ,naturally,refer to other authors and theatre or film directors,who got to the same conclusions,or who having published their works before,had influenced me.

You are among the contemporaries who didn’t influence me,but reached similar inferences,more or less at the same time.

For intance: your article in connection with Shakespeare was posted here in 2013. That was the time when I sent my first article to Ricardian Bulletin in which I already mentioned the misunderstood Shakespeare. I always regarded his Richard III a grotesque parody,the first ever perfect grotesque drama of world literature,but all the outrageous rubbish that was published in vulgar newspapers at the time of the discovery of Richard’s remains,urged me to make public what I’d always known. Maybe you were urged to do something because of the same reason. Anyway,we don’t ‘steal’ each other’s ideas,so we must acknowledge each other’s findings. I actually mention in my book that you wrote about the historic fact that the real Richard had the right to order Hasting’s execution. I read it here on your website.But I don’t know how to mention the exact reference. Could you,or could somebody help me giving me the exact place,how to quote it as a reference? I’d appreciate it.

Hi Eva. If you just need to reference my blog you are welcome to place a link to the article in your book. If you need to refer to the powers of the Constable they were modified by Edward IV to allow conviction and execution for treason on the basis of evidence the Constable had seen.

Thanks, Matt,but this book won’t be an ebook. It will be physical,so I cannot place a link,I’m afraid. How could I mention it as a reference?. For instance,as far as the chronology of Shakespeare’s plays is concerned,I found on a page: ‘how to refer to this article’. How is this in your case? It’s the publisher that persuiades me to find it,this is not going to be a self.published book. Thanks anyway

Eva, there is a new book out by Annette Carson which lays out very clearly the duties of the Constable of England. You can contact her by her website.

Hi Eva. Could you refer to it as;

Matt’s History Blog – Title of Blog Post (Published *Date of Publication*)

I’ve just checked,or rather spent at least an hour following links on your site.No way of finding the place where you analysed the duties of the Constable.If I click on ‘Hastings’,the article appears in which you say that the duties and rights of the Constable were explained in a previous post.But there is no link to that previous post!!!.And I don’t find it! The same thing happens as in the case of printed books.I mention the reference,but ‘by heart’,and I cannot find it to quote it precisely.In this case it should be easier, not the question of bying expensive books,and perhaps it may be interesting to you too that your site has this problem.if I type in the searcher anything,like Hastings,or Constable,or whatever,the present article comes back.Is it because I use a tablet,not a table computer?.Maybe.But couldn’t you give me that date when the article about the duties of the Constable was published?

Thanks,I know,but as my publisher also knows,I live in a pretty bad economic situation in Spain,so I simply cannot afford to buy expensive books on Amazon.Actually,my book would already be published if I could have put every reference in place.But I mention references without giving the exact page number etc,only having read the book years ago,or in Hungarian, which is my mother tongue.But for an English language edition,the page numbers and this kind of stuff has to be in English.I hoped that the american publisher would give some help understanding my situation,but they say that they cannot.I am trying to buy one or two books on Amazon,but it is not easy to catch the moment when there is a cheap secondhand one.On the other hand,I,m talking to another publisher and in the worst case,I would self-publish it.I am already an author on Amazon,you are more than welcome to check my author page.

Anyway,in the book about Shakespeare I don’t need many historic references,about Hastings Matt is enough.This thing about the link he mentioned,would be acceptable as a reference,if I find the concrete article and put the whole title that appears at the top of the page ‘https…’,that will do it,won’t it?

Thank you ,both of you,hopefully it will be all right.

Matt,what I am going to do about Hastings,is that I’m going to mention Annette’s book as a whole,and not finding the exact link on your site,I won’t be able to cite it. It’s a pity,because this is one of the most vital issues,and several references are better than only one.The Hastings scenes are very important,because I don’t want to insult either Richard or Shakespeare discussing that Richard didn’t behave like the character, of course not.This is out of the question. The point is that for Shakespeare and his knowledgeable contemporaries this was obvious.They understood the sarcastic scenes,only the brainwashed posterity could misunderstand so obvious things.I get back to Hastings several times in the book,this is why severa and exact historical references would also help,but something is wrong about the links on your site,this way it is difficult, if not impossible to find something.

I have al;ways believed More’s story was not intended to be truthful. He has Richard “meet” Tyrrel on the privy, which must be a code for ” a lot of this is s…”

Brilliant! Totally agree with this post.

Matt,here you mention Shakespeare,but I have the strong impression that you are very wavering about his oeuvre. I don’t understand why.For instance,in a previous post in which you praised The R III Visitor Centre,you started to discuss Shakespeare’s Richard III,as if it were ever meant to portray the real Richard. That Centre doesn’t desrve any praises,because they are only spreading these traditional misinterpretations insulting Shakespeare himself ,but naturally even more Richard

Hi Matthew,

This is another well written article, but aren’t there a couple more sources?

De Commynes – he writes very explicitly that Richard had the Princes killed. He also mentions Buckingham, but with the implication that they were working together. If he is correct, it would explain why the ‘rumours’ were so believable in 1483 when he joined the opposition.

Perkin Warbeck – he says that the assassin sent to kill him and his brother had second thoughts and let him (as Richard) go on the promise of not mentioning it.

Hi David. Thanks for reading and commenting. de Commynes is a source, yes. He knew Edward IV and Warwick personally but lost touch after he moved from Burgundy to France. He had never been to England and wrote for the French court who had a vested interest in painting Richard in a bad light. I guess the reliance placed in Warbeck depends on who you believe he was. His story required Edward V to be dead but Richard of Shrewsbury to have survived. I guess this is the beauty of it, weighing the unquantifiable.

This may be my last post here,because I want to delete even my own site on WordPress.Blogging is not for me,as I am not willing to use the so-called social media either.As far as poor Richard is concerned,I am trying to convince those Shakespeare would have called ‘the judicious’ones to look at the whole question from a totally different viewpoint.Most people are not only brainwashed, they are happy to be so.

Shakespeare portrayed this too.But most people just enjoy toying with Richard’s tragical story,as if it were a detective story.While it’s ridiculous to suppose that for instance,Buckingham’s revolt could be the result of the indignation caused by the murder of the Princes.Such a thing NEVER happened in history.People happily swallow what the propaganda of unscrupulous power suggests.If Richard had been as unscrupulous as his enemies,he could have committed any crime and then spread his version.Sadly,he didn’t. He seems to have been a representative of ‘patient merit’,e..g. silent merit that only receives ‘spurns’ from the unworthy. Why don’t people focus on Tudor’s proven crimes?Or on Shakespeare’s partly deliberate misinterpretation? On how it has served the interests of the establishment to direct everybody’s attention to a debate about Richard,not noticing at the same time that the posterior establishment goes back to Tudor whose villainy is proved by evidences.This is how brainwashing works,and this is why I am upset and tired to discuss this with those for whom it is a funny game to play the detective about Richard’s nephews,overlooking that they only do what the unscrupulous, victorious power have suggested.

You sound like you need to take a rest and refresh your mind with other matters! Sorry to hear you are feeling so bad.

From what you’ve said earlier about Shakespeare, sounds like you have some interesting ideas, worth developing.

Hi Eva. You sound very frustrated. You and I seem to agree about an awful lot regarding Shakespeare and it would be a shame for you to leave the public arena with your views. Have I done something to upset you or are you experiencing difficulties elsewhere? I hope your book is progressing well and look forward to its release.

Hi everybody

It is very nice of you to worry about my peace of mind.It’s not your fault,Matt,though you actually didn’t answer my latest question about the post I am unable to find on your site. I have enormous difficulties about the references in my book,and this way the serious. publisher won’t publish it.I even tried to contact some vanity publishers suggesting them that instead of wanting to take away my money for the publishing,we could make a different deal,that they help me with the references,publish it without my money,and then take away practically all the royalties.It shows that I am more interested in the cause than my selfish interests.But of course,these publishers do everything according to their routine.It doesn’t really matter,I don’t like them,the serious publisher or self publishing on Amazon is better.

What has recently stirred me up,was actually Word Press.I don’t want to leave the public arena,I really never used Facebook or Twitter.I only had a LinkedIn account,and I practically never signed in. until I deleted it a month ago these are very vulgar thingsto do self-publicity this way.Most people enjoy it because they enjoy dealing with themselves. I hate it.Strange thing,but I mention in my book about Richard,that I suppose that he fell victim of the fact that he wasn’t interested in PR either.He wanted to do the right thing and not to make propaganda to it.The few of us who are similar,understand it Those who saturate the internet with their grinning photos speaking about themselves on Facebook all the time,don’t.

So,recently I tried to set up a website on Word Press,and I found out what I posted yesterday.I am going to set up a site elsewhere where it can be a website,not a blog.

Thanks anyway,Matt,if you could give me the answer to that question about the posts that don’t appear if I write the subject in the searcher,I would appreciate it.

Hi Eva. I will have a look when I get home later.

It sounds to me like Amazon self-publishing might be a route forward. It’s free and easy.

Oh,sorry,here in my post yesterday,I didn’t go into the details.So:the problem with WordPress is that once they drag you into signing up,and you don’t want to be a blogger,you are between a rock and a hard place. You either set up a blog,or you have to pay even to have direct email help.Websites are for money.So you either blog,or keep your account which is good for nothing,or pay for a website.I don’t like this.That the searcher isn’t quite right on your blog,maybe the fault of WordPress too.

I can’t get on with WordPress either. I set up an account, because seemingly you can’t reply to other WordPress blogs without one. But I find it awkward to use so haven’t done.

Right now,I’m still trying to put the book together,with the correct references and publish it with the original publisher,which is a good,’traditional’ one,not one of these that only want the money of the authors. these ones are just like Word Press,it seems. If you are signed up,and you don’t want to be a blogger,you either hang yourself up,or start blogging. The only option left is to pay to them.

O. K. So ,if you can help me a little,Matt,that would be great. I’ll publish my book anyway,and I’ll set up a normal website somewhere,not a blog. But if I have to publish the book myself,the problem will be the same as with the other books I have on Lulu (in Spanish) and on Kindle Direct in English. They have little publicity because I have always denied the facebook sort of self-publicity. On Facebook I even tried to set up a professional site as a writer,and their system says:’you’ll have to manage this site from your personal one’. They take it for granted that absolutely everybody has a personal Facebook site. This is very sad.They are unable to imagine that some people exist who focus on causes,not themselves.

Hi Eva – You contacted me asking for source references and I helped you at some length with your first enquiry; then I said what you need to do is make a FULL LIST of all the other references you need, which you can then send to me and other knowledgeable people. I’m sure we will all do our best to help. However, people like us are always busy with projects of our own and I’m sorry that I for one cannot read your manuscript as you wanted me to. If the references are the only thing preventing you being published, I’ve told you how you can solve the problem. But you need to be succinct – just make that list, OK? 🙂

Hi,Annette

Thanks.I’ll send you a personal email,just like before.Actually I sent you one about 10 days ago to which you didn’t answer,perhaps you didn’t receive it.I was sort of misunderstood here,because when I supposed that this would be my last post on Matt’s blog,it was only because I thought that WordPress wouldn’t let me go on,once I delete

the site I started to set up,but I don’t want to publish,because I don’t want a blog.I always preferred websites and personal emails.Blogs are all right,if someone likes working on them,Facebook and Twitter don’t even seem all right to me.They infest the internet with all these ‘likes’ and ‘follow me’,superficial, vain things.

I only suggested my manuscript to you because there are ideas in it for historians to research from the relatively new point of view. that after all not me,but the misunderstood Shakespeare suggests.I am only his ‘medium’.He can BOOST the Ricardian cause.

This is an excellent appraisal of the sources and evidence, well and logically argued article, one of the best balanced assessments of the disappearance of the so called princes in the Tower I have read for a long time. It is important to remember that no evidence of murder, let alone the killing of two young boys, Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, by any individual exists.

I have a great administration for Sir Thomas More, but his history cannot be taken at face value. History as we know it today was written quite differently in 1516. For one thing an author would be writing often to please a powerful patron, in this case, probably King Henry Viii. Chronicles were also written to reflect happening from a certain bias or standpoint. Rumour and conjecture were not always seperated from fact and literature experts believe that histories often contained elements of other earlier well known stories. For example, mythology and morality tales could find their way into later chronicles. The so called facts in More, apart from being challengable contain allegory, drama, political agenda, hearsay, imagination and source information possibly gained from a patron in whose household he spent several years, Cardinal Morton. Some people even use More today to claim that the bodies in Westminster Abbey are the princes because their bodies were found in the place that More said that the bones were buried. This ignores that More also stated that the bones were dug up and moved to a more suitable burial place. If More is correct, the bodies in Westminster Abbey are not the Princes. Supporters of More as a factual, if late source cannot have it both ways.

As for the numerous scholars and others sources, they are divided about the fate of the Princes, if Richard iii was guilty, bssed on rumours, in some cases fanciful and contradictory in content, give alternative suspects and are not eye witness accounts. Richard iii did not have the most to gain, having recently read more about this, it is clear that he did himself a disservice by their deaths. They were not adult monarchs who had been displaced by someone who had been called upon to replace a failure or tyrant, but unproven, innocent children, set aside due to allegations that their parents were not properly married. Richard had no reason to kill them, not at this point and the deaths would tarnish his shakey reputation further. Richard had acted ruthlessly, if lawfully, to set aside clear and present dangers, threats and opposition to him as Protector; he was now accepted as King, he was freely offered the crown, he was given wide open support; he was lawfully crowned; Richard could not risk all that by the foolish act of murder of two children in his care.

What did happen to Edward v and Prince Richard? The truth is we don’t know. If they were killed, a number of people can be seen as suspects, including Margaret Beaufort, Henry Tudor and Buckingham. No contemporary evidence or modern evidence has yet emerged to convict anyone. No evidence that the boys were killed has been confirmed. Trolls on Twitter like to accuse every famous person who ever lived as being a child killer or of sexual abuse, without any evidence whatsoever. Should we believe what they say, or thoroughly and impartially investigate these allegations and conduct a proper trial? Condemning somebody from history without evidence is the same thing. Richard iii and anyone else deserves a fair hearing, especially when no crime can be found to have tsken place.

Did the boys die of neglect, fever, plague, the sweat, other disease? Where they moved to another place before Bosworth but Richard and others knowing the information killed before the place became known? Did they escape and did one reappear as Richard of York, called Perkin Warbeck or Lambert Simnel under Henry Tudor? There are several possible outcomes to their fate.

If they were killed why hide this? Two excellent reasons have been suggested. One is self recrimination. If the killer either Richard or Henry risked a backlash. For Henry, it also created problems as the true heirs survival would place his own right as King into grave jeopardy. For him silence worked well…For both kings the cult of personality was strong. Having a religious cult grow up around the boys served to challenge and make problems for the peace of the realm and political control may also be undermined. Richard iii had seen this problem with the movement and elevated status of Henry Vi. Nobody wanted the boys either declared saints or confirmed to have died in suspicious circumstances. Ridiculous as it may seem, silence and apparently not knowing was the best option for both Richard iii and Henry Vll.

Finally, just to conclude, this case is a cold case and open to interpretation. Nobody knows what happened to the Princes, we don’t have all of the facts, we may not even have any bodies, and, unless something radically new turns up which settles the matter, we may never know what happened to them. In that case Richard iii is innocent unless proven guilty.

Thank you for reading and for your kind words. I agree that in the absence of real evidence no crime, let alone a perpetrator, can be proven beyond a doubt. The misinterpretation of several sources is worryingly prevalent and used to reinforce interpretations that simply don’t stand the test of the actual sources’ content.

Just a p.s…a question. Should we even call them the Princes in the Tower, as if illegitimate tjey could not succeed? I understand Richard’s declaration is sometimes challenged, that he acknowledged that Edward was King for several weeks before the evidence came to light, but then he was lawfully replaced basef on the contract evidence that Richard had about Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV and Eleanor Butler. Henry Vll then reversed the Act of Parliament, ordered all copies to be destroyed, so he could marry their sister, Elizabeth of York. However, at the time of their disinheritance, move to royal but secure custody and disappearance, they were illegitimate. So are they really Princes or do we merely refer to them as such as a modern politically correct convention?? What do you think?

I know John Ashdown-Hill argued strongly that they shouldn’t be called Princes at all. I’m not sure it matters too much. They were before June 1483, weren’t after it and were again once Titulus Regius was repealed. It depends on your point of view regarding the pre-contract but is semantics really – it doesn’t matter too much how we refer to them I don’t think and Princes in the Tower is how they are widely known now.

Hello Matt, thanks for your response. I guess you are right, after 500 years, their title does not matter, we know them as the Princes, what matters is hoping one day the truth comes to be found.

Personally, I don’t refer to Edward IV’s sons as princes, they were either Edward V and the Duke of York (and Norfolk) or the sons of Edward IV, which isn’t in dispute. However, I don’t refer to their sister as Elizabeth of York, she was either the legitimate daughter of the late king (so a princess of England) of the illegitimate daughter of the late king, he wasn’t just the Duke of York when she was born. Henry Tudor’s claim to be heir of Lancaster wasn’t really valid.

I. wonder why Edward is called Edward V.It was Tudor’s interest to turn him into a king,Richard into a usurper and himself into a saviour.

The other thing is that it is still the same way on Matt’s blog,I cannot find whatever I search using the searcher.I tried to just go back and have a look at all the previous posts,but it is too time consuming this way.

Hi Eva, I think it was because he was King for a number of weeks before the information concerning the alleged contract between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot Butler. Even Richard acknowledged young Edward as King, swore allegiance to him and had the other lords do the same. Richard started out as Protector of the Realm, to protect and defend his charge, the young king. He only made the decision to accept the crown once the clergy stepped up and came clean on what they knew about Edward IV and his marriage entanglements. As before mid June from the moment of his father’s death young Edward had been king, he was regarded as such. It was only after Richard iii has been told the truth and the sermon on June 24th at Saint Pauls that he is no longer King. Richard regarded Edward as Edward v before the truth, but not after. Henry Tudor of course reversed the legal status of the Princes, their sisters, partly because he was seeing his actions as lawful and Richard’s as not, partly because he was to benefit from this. With Henry Tudor going to marry Elizabeth, she had to be legitimate. The ironic thing was that by reversing the Parliament Act, by reversal of Elizabeth’s bastarization, Henry Vll also legitimized her two brothers. Now how lucky for him they had vanished ( not condoning murder of course). I don’t believe Henry Vll killed them either, but it does put a different complex on the whole question of who benefits more….Richard or Henry or somebody else?

I must mention here that since our exchange of messages last week,Annette Carson very kindly helped me with some concrete references.I’d like to thank her publicly here.

It really means very,very much from the point of view of the possibilities of publishing my book.

As far as you are concerned,Matt,perhaps I will mention this January article of yours as a reference.I don’t want to leave you out of this,because you are one of the few people who think more or less the same about Shakespeare as I do.And Shakespeare is of utmost importance.If he meant the opposite of what most people have thought for centuries,it changes everything in connection with this subject.

Ricardians seem to be a little afraid: what happens if one day someone. finds an evidence of Richard’s guilt in connection with the disappearance of his nephews?Shakespeare,the misunderstood Ricardian playwright suggests: NOTHING.

I am of those who think that Richard havinge was a much better,perhaps saintly person than most rulers..Shakespeare portrayed that these are the tragical losers of history.He would have never committed premeditated murder even you can imagine him capable of,Matt.But if,according to his duty,as Constable,he let some people carry out the orders of the king,and later when he himself became king,he had to do with the disappearance of the boys—well,then he was not saintly. In this case he was like other kings.Still,the focus of everybody’s interest should be the campaign of slanders against him by people who even in this case were much worse than him The slanderers are the bad guys..Shakespeare portrayed this,his age is full of not researched secrets.

It is a pity that Annette who didn’t only helped me a !of,but she is also an excellent historian–that she is not very interested in the Elizabethan Age.But you,Matt,interested in the 16th century and Shakespeare,you can do much historic research of this age,that I cannot.These three things,research of the 15th century,that of the 16th,and setting right Shakespeare’s interpretation, all together can ensure that even in the highly unlikely case of Richard having done some of the bad things he is accused of,those of the Tudor ‘party’could not roll on the ground roaring with laughter.Shakespeare helps us look at the whole subject differently

Glad you are now able to progress, Eva. Your book sounds very interesting. Perhaps you could let us know, eg by posting here, when it is published.

Yes,I am very grateful to Annette,I have no money to buy expensive books on Amazon,but she helped me with the references.Thanks for your interest,in the meantime you can read my article on Queen Anne Boleyn about Shakespeare’s most misunderstood play,Richard Iii.I insist on this so much because of what I mentioned in my previous post.Sometimes I have nightmares thinking of the unlikely,but not completely impossible case:how the Tudor admirers would enjoy if a document were found proving that Richard was ‘guilty ‘ in the death of his nephews.Right now it would be catastrophic for the Ricardian cause.Shakespeare’s misinterpretation and what his ouevre portrays puts the whole thing in different light.

Eva, have you tried looking on archive.org for material you need? It’s all free and can be downloaded free as pdf’s. I find it a very useful site. It may not have everything you need, but you might also find some things you hadn’t come across before.

Don’t forget to try Inter-Library Loan – ILIAD. You can have books sent to your local library from almost anywhere that participates. I’ve gotten to read a good many that I never could have afforded to buy – several from more than 1000 miles away. It’s free too!

Thank you,Matt,I will check it.I already took some references from the internet,but not from this site.And with the ones Annette was so kind to give me,I practically have no real problem with the reference s any more.But I still don’t want to leave you out of the whole thing,because of your interest in Shakespeare. The fact that he was misinterpreted in itself shows that our cause is the rightous one. The credulous public was misled about everything just to serve Tudor,and it keeps on being true either way.If Richard was totally innocent ,practically a saint,or if he did wrong things,like according to Shakespeare ,all,even the good and much loved kings.More about this in my book,and on my website.Maybe I give in,and set up a blog here,because Word Press does not let me go. I cannot delete the account.I have very much to say about this and my other important subject,the animal cause too,so I need either a webpage or a blog.I had a webpage before,I prefer it,but…

I get on well with Blogger. I find it easier to use than WordPress. What is the animal cause?

The animal cause is the fight for animal rights,like that of PETA or the Dodo.I am on the newsletter list of both organizations.Of course,there are many more,here in Spain too.My Spanish book which is on Lulu,is of essays about this.I try to bring it over to Kindle Amazon where I have a thriller having to do with Ancient Egypt.All the publicity to sell them would be much work,I have to finish my Shakespeare book,so I am not keen to become a blogger…

Thank you everyone who kindly gave me advice to get some references.As far as young. Edward is concerned,he was never anointed and crowned. I wouldn’t say that’even’Richard considered him a king.For me this is a strong evidence of. the fact that Richard was honest.He thought that Edward would be the king,he didn’t want to change this situation.He already treated the boy as a king,but when it couldn’t be,Edward didn’t become really a king.Shakespeare deals with similar situations in his ouevre showing that not everyone is power thirsty.

I joined the Richard III Society a year ago and have learned so much about the period and characters yet there is so much more to read. I have just finished your excellent book on the War of the Roses and the final chapters on Richard and Edward V had me thinking. When Richard met up with his nephew Edward (in Northampton?) to escort him to London and his coronation, is it possible that Richard suspected the boy was not actually Edward? I believe Edward had been away for some time, could he have died and been replaced to preserve the Woodville power base? It could explain some of Richards actions at the time and later in London. I would be fascinated to know if anyone has considered this.

Hi. Thank you for reading my blog and I’m thrilled that you enjoyed the book.

Richard had been in the north and Edward V in Ludlow on the Welsh borders for many years so they probably didn’t know each other well. There is no suggestion the Richard thought Edward was an imposter in the sources. I think it is more likely that Richard suspected the motives of the Woodvilles and their influence over Edward and was keen to prise him from them. Anthony Woodville had been acting slightly suspiciously just before and after Edward IV’s death. Mind you, anything is possible and worth exploring!

If you get a chance I would really appreciate a review of the book on Amazon or somewhere similar.

Thanks again for reading.

Matt

Review done – fives stars!

Thank you very much! I really appreciate it.