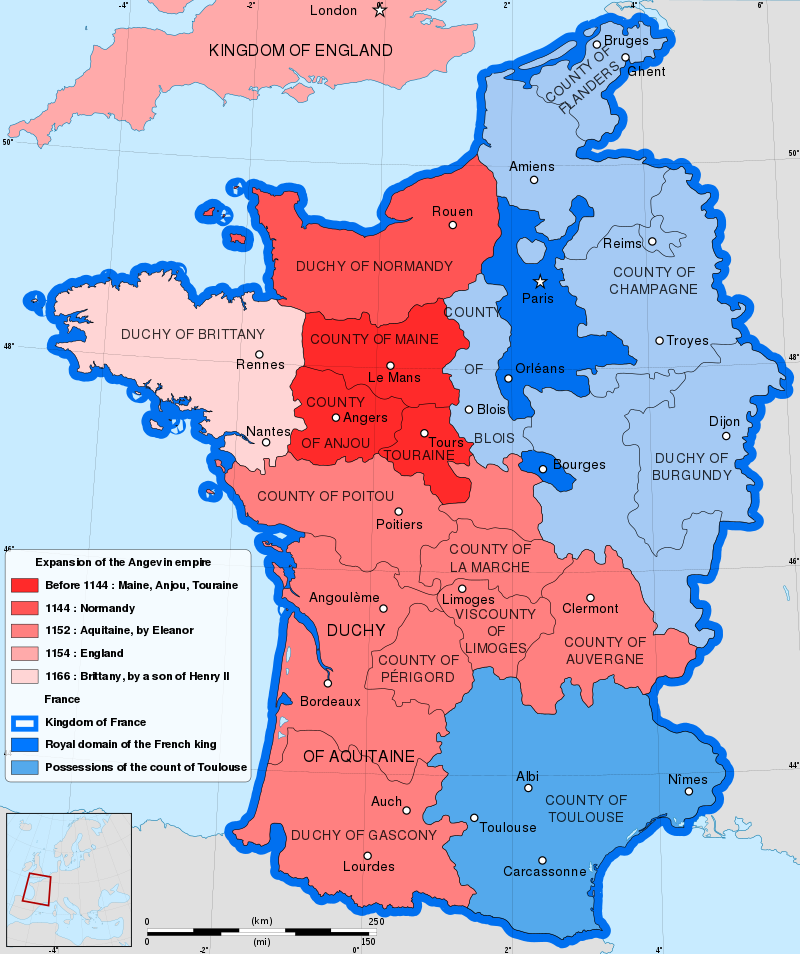

My next book – due for release in October, all being well – is about Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. They were one of Europe’s most fabulous power couples, ruling lands that spread from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. Eleanor was nine years Henry’s senior. When they married in 1152, he was a brash nineteen-year-old, already Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, and planning to add the crown of England to his already glittering haul. Eleanor was twenty-eight, and until recently had been the Queen of France. Her first husband, Louis VII of France, had arranged for their marriage to be set aside on the favourite grounds of consanguinity – being too closely related. He had failed to foresee her swift remarriage to one of his most impressive and therefore threatening subjects.

Everything had come to Henry easily in his teens. His father, Geoffrey the Handsome, Count of Anjou, had conquered Normandy and handed it to his son, and with Geoffrey’s death in 1151, Anjou had also come into Henry’s possession. If his start had been impressive, the rest of his life was to be a story of epic successes, heartbreaking setbacks, war and high politics. By the time of their marriage in 1152 though, Eleanor already had a vast wealth of experience behind her. Although the vast territories of Aquitaine and the chance to get one over on Louis must have formed part of Henry’s thinking in accepting the match, this intimate familiarity with power, particularly royal authority, probably contributed to Eleanor’s appeal too. Before Henry was out of his teens, she had already lived through more than most would see in a lifetime.

When Louis VII committed to lead the Second Crusade in response to increasingly desperate pleas from the Holy Land for help defending Jerusalem and the states founded by the First Crusade, Eleanor went with him. Many chroniclers point to the king’s puppy-like adoration of his queen, but by 1147 when the host became the journey east, their relationship was not as rosy as it had seemed at first. Louis was a complex character. The second son of Louis VI, he was not born to be king, and his initial education had been a cloistered, religious one. Wrenching him from the surroundings left a deep scar, and the early exposure to the Church’s dislike and distrust of women similarly never healed. Eleanor would famously remark that she feared she had married a monk rather than a king. If Eleanor remained in Paris, she would have a claim to regency powers, and Louis preferred his old mentor Abbot Suger to rule without the potential for a power struggle. Taking Eleanor was more about getting her away from Paris than fear of missing out on her company.

The crusaders left Paris on 11 June 1147, travelling via Metz, through Bavaria, taking two weeks to cross Hungary and arriving at Belgrade in Bulgaria in mid-August. They had been in touch with the envoys of Emperor Manuel Komnenos of the Byzantine Empire, Passage through Constantinople was vital, but the emperor was wary of the approaching army. The king and queen arrived in the fabled city on 4 October. They spent three weeks as the emperor’s guests, staying at the Philopatium, a favourite imperial hunting lodge. The lavish, comfortable surroundings allowed them to recover from their journey and prepare for the hardest part that was still to come. The lighter atmosphere may well have reminded Eleanor of her home in Aquitaine, a bright memory undimmed by the drab, sober dullness of Paris.

Before the end of October, the army crossed the Bosporus and entered Asia. They almost immediately came under frequent, probing attacks as they marched onward. In early January 1148, disaster struck, and Eleanor’s reputation began its tumble into scandal and, let’s face it, lies. On 6 January the crusaders had to cross Cadmos Mountain. It was a logistical nightmare for such a vast army under constant pressure from the Seljuk Turks. Command of the vanguard, leading the crossing, was given to Geoffrey de Rancon, a Poitevin and a vassal of Eleanor’s. The plan was for Geoffrey to reach the peak and wait for the rest of the army to avoid them becoming too strung out. When he got there, Geoffrey found there was not enough room for the remainder of the force and moved on to make space for them. The Seljuks took advantage of the situation and attacked the army as it stretched along the mountain roads. It was a slaughter, Louis himself was in grave danger, and forty of his bodyguard lay among the dead. For those increasingly hostile to the Poitevin queen, the failure of one of her vassals was all the ammunition they needed to blame Eleanor for the loss.

The next stage of the journey was no less perilous. Louis paid Greek guides at Attalia to lead the bulk of the army across land while he, Eleanor and some of his men sought safe passage by sea to Antioch. The three-day journey took a fortnight as the fleet was buffeted relentlessly by storms. Only about half of those who marched out of Attalia reached Antioch alive. The Greek guides had taken the king’s money and betrayed his men. The bedraggled force, described by John of Salisbury as ‘the survivors from the wreck of the army’, were at least safe in the embrace of Antioch. Prince Raymond, the ruler of the Frankish outpost, was Eleanor’s uncle, and the chance to see a member of her shrinking family may well have been part of the lure of the Holy Land to Eleanor. Louis and Raymond appeared to get on well, and the time to recuperate was just what the king and his army needed.

Raymond was desperate to obtain Louis’s help with an assault on Aleppo. It was, the prince explained, a critical step in regaining Edessa, the stated aim of the crusade. Louis, quite possibly already disillusioned with the idea of crusading, was focussed only on reaching Jerusalem to complete a personal pilgrimage. Louis, according to John of Salisbury, became annoyed when ‘the attentions paid by the prince to the queen, and his constant, indeed almost continuous, conversation with her, aroused the king’s suspicions.’ He decided to leave Antioch, but Eleanor expressed a wish to stay with her uncle, backing his strategic desire to attack Aleppo. Raymond offered to keep Eleanor safe ‘if the king would give his consent’, but Louis most assuredly would not. John of Salisbury’s is the earliest account of the rumours that grew from the disagreement, though he never quite gives full form to the story, nor comments on its veracity. He wrote that one of Louis’s secretaries, a eunuch named Thierry Galeran, who was frequently mocked by Eleanor, suggested that ‘guilt under kinship’s guise could lie concealed’. Driven to distraction, Louis packed his things in the middle of the night, and Eleanor was ‘torn away and forced to leave for Jerusalem’. John concluded that this was the beginning of the end of their relationship. Eleanor questioned the validity of their marriage on the grounds of consanguinity, and ‘the wound remained, hide it as best they might.’

It is from this episode that the rumour later emerged, developed and became entrenched that Eleanor had engaged in a sexual relationship with her uncle at Antioch. It was misogynistic mud-slinging: why else would the queen defy the king, a woman rebuke her husband? It was outside the accepted norm, and it never really occurred to them that Eleanor might have her own mind, her own ideas, and, heaven forbid, a better tactical grasp than the king. Clutching around for an explanation, sex was the only one the men writing down these events could settle on. Women were, they believed, driven by an insatiable lust that caused them to try and lead men astray. Eleanor must have seduced her uncle Raymond and been inspired by lustful desire to defy her husband. Essentially, it meant that the whole mess that the Second Crusade was becoming could be blamed firmly on Eleanor. She had ruined what the men, led by her husband, would have made glorious otherwise. If they had been forced to consider the failures of the king, of the men, or the possibility that God had abandoned them, it opened a whole can of worms. That slippery meal was neatly avoided by blaming Eleanor for being a woman.

For centuries afterwards, this affair was largely accepted as fact and Eleanor’s reputation accordingly tainted. William of Tyre was less discrete than John of Salisbury, writing of Raymond, Louis and Eleanor: ‘He resolved also to deprive him of his wife, either by force or by secret intrigue. The queen readily assented to this design, for she was a foolish woman. Her conduct before and after this time showed her to be, as we have said, far from circumspect. Contrary to her royal dignity, she disregarded her marriage vows and was unfaithful to her husband.’ This is the view of Eleanor that persisted, and which accompanied her into her second marriage to Henry. It coloured the view of all of her actions afterwards, but there is no evidence that it is even remotely true.

Louis and Eleanor reached Jerusalem in May 1148. When a council meeting, held by King Baldwin II and attended by Louis, met on 24 June, it was decided that Damascus would be the first target. Raymond and the Count of Tripoli refused to participate in the council meeting, preventing a fully coordinated Christian effort. Still, on 24 July, a month after the meeting, the army arrived outside Damascus. The inhabitants immediately appealed to Nur ad-Din for aid and a vast army was sent to relieve the city. Four days after their arrival, the Christians packed up and left. Louis stayed on in Jerusalem for a while, touring the religious sites. He and Eleanor spent Easter 1149 in the city, at the locations of the crucifixion and resurrection. It was surely an experience to savour at the end of a disastrous expedition.

In April, after increasingly pressing letters from Abbot Suger urging Louis to return, the couple left Jerusalem for Acre. They crossed the sea in separate ships, perhaps a symptom of their worsening relationship. The convoy was attacked and scattered. Louis landed at Calabria, but Eleanor reached land at Palermo, apparently ill. She took several weeks to recuperate before rejoining Louis. The couple made their way to Tusculum, where they visited Pope Eugenius to debrief him on the failures of the crusade. During the visit, Eugenius forbade the couple to mention their consanguinity ever again and provided a bed for them to sleep together in while they stayed with him. Nine months later, they had a daughter, but it was not to save their marriage.

The experience of the Second Crusade must have left a deep mark on Eleanor. She had travelled halfway across the known world, to the place considered the centre of the world. She had endured hardship, faced the mortal peril of battle and constant guerrilla attacks, enjoyed the surroundings of Constantinople and Antioch, where she met her uncle. She had become the increasing focus of an effort to apportion blame for failures, from a vassal disobeying instructions in the mountains to the allegations she had been sleeping with her uncle. In Jerusalem, she had found herself at the religious heart of the world in a profoundly spiritual age. She spent Easter at the very spots Jesus was crucified and resurrected. The journey had ended with the Pope all but forcing her into her husband’s bed to conceive a papally approved child. All this, and she was just twenty-five when she got back to France. Somehow, though, this was not to prove the most dramatic experience of her life. Young Henry was looming on her horizon, and her life would never be the same again.

Sounds really good Matt, you definitely hooked me in. I’ll look forward to being able to read your book, hopefully later in the year. Well done.

Can you get it out by July Matt? I cannot wait til October! Eleanor was one of my NO1 favourites from Englsih history – what a woman. I sometimes wonder about the life of her sister Petronella, living in the shadow of such an incredible sibling. Very best of luck with book – will be axiously waiting to get a copy. . – Wendy

It’s with the publisher Wendy, but I don’t think it can be brought forward unfortunately. I hope I do Eleanor justice.

Certainly sounds absolutely fascinating.

Great article, Matt. I have often wondered about the alleged affair of Eleanor and her Uncle, which would have been incest, not just adultery and yes, years ago would have believed it, but it’s another one of those scandals which are often made against Medieval high born ladies of strong personality and their own ideas. Men wrote the history, men had the power, men kept the sources, men made the rules. Eleanor didn’t always play by the rules and medieval men were challenged by her. Her Courts of Love were famous, if just romantic. A scandal would play into the agenda of those who wanted to challenge her political power. I look forward to reading more about that and her achievements. Looking forward to your book.

Great News I always enjoy your books as your research is so thorough-LOVE Eleanor so looking forward to this

Feeling quite jipped that I’ve just discovered your books! Read so much on these subjects in particular time. War of the roses Edward the fourth etc. etc. thought I was actually bored until I read a bit of your blog and a bit of the interview and some synopsis/forward on your works and now I’m all fired up again couldn’t be more pleased . I hope to see your name rise off in the realm of other British authors of historical and regular fiction that we get more press on here in America it’s a tough market I think but a little google headline about the princess in the tower Is a massive testament to your efforts at promotion- keep going and all the best of luck!

Hi Tiffany. I’m glad that your interest has been rekindled. I hope you find my books interesting and they offer a different view of this fascinating period and the incredible characters who lived through it.

When can we expect the book about Eleanor The Crusader to be published?

Hi, Matt!

Thanks so much for your writing here, really fantastic.

Is your book available? Our family lineage has been traced back the Queen and her sons Richard and John and I am just SO fascinated and enthralled in the whole story!

Hi. It should be available in most locations now. I hope you enjoy it if you find it!